Chapter 1: Poverty and Prosperity

War and My Grandmother

Thirty years before the birth of “Pokémon GO,” I was born in a remote village in Heilongjiang Province in northeastern China. To explain why I was born in China, I must first begin with my grandmother’s story.

My grandmother, Shizu Nomura, was Japanese. Born in Obama City, Fukui Prefecture, she traveled to Manchuria in 1935 as part of the Manchurian colonization movement, following her brother Kikujiro. She was one of approximately 270,000 Japanese who went to the former Manchukuo between the 1931 Manchurian Incident and the end of the Pacific War in 1945, under the slogans of “Land of Righteous Harmony,” “Harmony of Five Races,” and “A Dreamland Paradise”1. After arriving in Manchuria, my grandmother met and married Hidekichi Kobayashi, a Japanese man who worked for the Manchurian Railway. She had three children with him and was living a comfortable life. However, this peaceful existence did not last long. In 1945, Japan accepted the Potsdam Declaration and the war ended. Since my grandmother’s brother and husband had been drafted into local service before the end of the war, my grandmother and her husband were separated at the time of surrender, with neither knowing if the other was alive. Many others were in similar circumstances. Left behind, my grandmother fled through mountains and fields with her three children in terror. In the extreme cold of Manchuria, where temperatures could drop below -40°C in winter, her three children died one after another from cold and hunger. My grandmother herself lost most of her toes to frostbite. Exhausted and in despair, she collapsed in a mountain hut. It was my grandfather who found and rescued her. My grandfather was a Chinese man named Shi Xiangchen. After meeting my grandfather, my grandmother gave up on returning to Japan and decided to live in China, marrying him. Eventually, she had two children with my grandfather, who became my father and uncle.

In 1953, eight years after the war, my grandmother sent a letter to her family in Japan. Her family had assumed she had died and had already registered her death. They were overjoyed to learn that she was still alive. Afterward, my grandmother exchanged letters with her family every two to three years to inform each other of their situations. However, contact was lost again during the turmoil of the Cultural Revolution, which began in 1966.

In September 1972, Prime Minister Kakuei Tanaka visited Beijing, China, and along with Premier Zhou Enlai, issued the Joint Communiqué of Japan and China, establishing diplomatic relations between Japan and the People’s Republic of China. That same year, a letter from my grandmother reached her family in Japan again. By this time, my grandmother was already 58 years old and suffering from cervical cancer. As the medical technology in China at that time was insufficient, she informed her family that she wanted to return to Japan for treatment. Since her death certificate had already been issued, the paperwork took time, and her wish was only fulfilled in June of the following year. By then, my grandmother was in a condition where she could die at any moment, but out of a desire to set foot on her homeland’s soil one last time, she decided to return to Japan. As there were no direct flights from China to Japan in that era, she needed to go through Hong Kong, which was then a British territory, to reach Japan. Since my grandmother was no longer able to travel alone, my father decided to accompany her part of the way. It was a long journey of several days from the rural area where my grandmother lived, through Harbin, then to Beijing, Guangzhou, and Hong Kong. By the time they reached Beijing from the countryside, my grandmother was already too exhausted to move much, so my father carried her on his back while searching for accommodation. Without money, my father and grandmother couldn’t find a place to stay and ended up spending the night in the waiting room of Beijing Station.

The next day, when my father and grandmother visited the Japanese Embassy for paperwork, they received generous assistance. The embassy arranged sleeper train tickets to Guangzhou and Hong Kong, and even sent them to Beijing Station in an official vehicle. At that time, only officials and foreigners could ride in sleeper trains, so my father still expresses gratitude to Japan for this to this day. My father couldn’t go beyond Guangzhou, so he was worried about what would happen, but they met two Japanese people on the sleeper train who agreed to help my grandmother for the rest of her journey to Japan.

My grandmother’s return to Japan after 32 years was such a significant event that it made the newspapers. Here is an excerpt from a newspaper article from that time:

Tearful Homecoming from China - Woman from Obama

Tuesday, July 17, 1973 Newspaper unknown

Separation from her husband, the death of her beloved children, and remarriage to a Chinese man… A woman from Obama City who went to China as a member of the Manchurian colonization team before the war and had the tragedy of war etched into her entire being has recently set foot on her hometown soil after more than 30 years. “I’m truly glad to be alive.” A tearful reunion as she embraced her brother, sister, and mother. However, now she is continuing treatment at a hospital in Maizuru City, suffering from a serious illness.

Although she had returned to Japan with the last hope of her life, my grandmother wished to see her sons whom she had left in China one more time. She continued treatment at the hospital, but her condition was already terminal, and after about two months, she passed away surrounded by her family. Here is another excerpt from a newspaper article at that time:

Returned to the Soil of Her Birthplace

Saturday, August 4, 1973 Newspaper unknown

Returning from China after more than 30 years, Shizu Nomura (58), a native of Kamikatsuragi, Obama City, who had been fighting a serious illness, passed away on the first day of August at Maizuru Municipal Hospital where she was hospitalized. A quiet funeral was held in her hometown of Obama City on the third. It was just over a month after her return, but watched over by her mother and siblings, she finally returned to the soil of her birthplace.

If it weren’t for the war, I would never have been born, but I sincerely believe that war, which sacrificed so many people including my grandmother, must never happen again. This peaceful era in which I was born was built upon the sacrifices of those who came before us.

Born in China

A few years before my grandmother’s return to Japan, my father and mother got married. After having four girls in succession, I was the fifth child, a long-awaited boy. The name given to me then was “Shi Lei (石 磊).” My mother had decided on this name before I was born if the child was a boy. It’s a very strong name with four stones in its Chinese character, containing the wish for me to grow up to be a robust child. I’m often told I’m stubborn, which might be the influence of this name.

China was implementing its one-child policy at that time, so my parents paid fines each time a child was born. Originally, our family didn’t have much money, so by the time I was born, our household was already unable to pay the fines. Eventually, instead of fines, our household goods were taken away. My parents somehow managed to scrape by, but to improve the situation, when I was two years old, my father went to Japan to work, relying on my grandmother’s relatives.

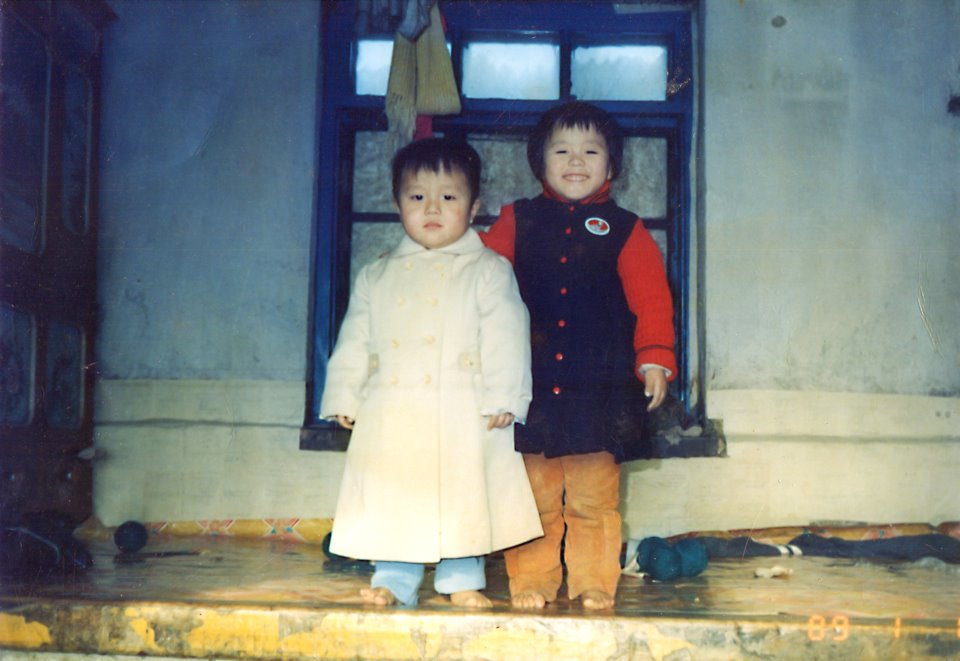

My one-year-older sister and me at home

My one-year-older sister and me at home

I don’t remember that time, but my father, who had returned from working abroad, bought us new clothes on New Year’s Day 1989. The photo above shows me and my sister, who is one year older, wearing the new clothes our father bought us.

It’s not hard to imagine that our life improved at that time, since we could even take photographs at home. I also remember having a Japanese stroller at home. We had a black and white television set with a dial to change channels. It was the kind of TV that could be fixed by hitting it when the image became distorted, and I heard that neighbors often came to watch it. However, this situation didn’t last long. My father was swindled out of the money he had earned in Japan, and we fell into an even deeper poverty than before. Pushed to the edge, my parents sold our brick house and moved to a house made of straw and mud. Being made of mud, the walls had holes that became nests for mice. Newspaper was pasted on the mud walls as a substitute for wallpaper. I was about three years old at the time.

Given this situation, from the time I became conscious of my surroundings, our family was poor. We were so poor that we struggled for food, and I was often hungry. We didn’t have rice at home, so our staple food was corn porridge. Don’t imagine this corn porridge to be like the corn soup available today. It wasn’t such a delicious thing; it was something that barely had any taste. I hated this corn porridge. I would often trouble my mother by saying, “I’m not hungry now, so I’ll eat more when we have white rice.” We couldn’t afford candies or snacks, so I would often put water and sugar in a bowl, leave it outside overnight to freeze, and then lick it. We couldn’t afford toys either, so my father, who was good with his hands, would cut wood to make toy guns and such. We didn’t have insect nets, so we’d attach spider webs to forked branches to catch dragonflies. In spring, I would go with my sister to take flocks of chicks and ducklings to the riverbank to feed on insects, and in summer, I would play riding pigs in the garden. When the Chinese New Year came in winter, those pigs would transform into dumplings. Though it was sad for my child’s heart, the dumplings that could only be eaten once a year were an incomparable delicacy.

After moving to the mud house, my parents started a tofu business. Making tofu required early mornings, with preparations beginning at 2 or 3 AM. I often got up early to peek at my parents’ work, looking forward to the soy milk that was made during the tofu-making process. In the morning, once the tofu was ready, I would go with my mother to sell it, pushing a cart and calling out, “Doufu, Doufu.” Around the same time, my father started working as a driver for the only police station car in the village. Gradually, our economic situation improved. Eventually, a color TV arrived at our home, and then even a telephone was installed. This phone wasn’t one where you input phone numbers; first, you had to turn a handle on the phone to connect to the exchange, and when you told them “so-and-so’s house,” the operator would connect you. I remember finding it strange to see my father repeatedly bowing when he made long-distance calls to Japan several times.

My father was good with his hands and skilled at working with machines. Perhaps influenced by him, I also liked looking at machines, taking things apart, and making things. Before entering elementary school, I made my own sled from wooden boards and repaired broken doors. I also liked cars and would often go look when I heard the sound of a car near our house. My mother was always doing sewing work, which I also often tried to imitate by watching. Here’s an anecdote I heard from my mother:

Once, when a button came off my clothes, I sewed it back on myself. However, I sewed it in a way that closed the edge of the clothes, making it impossible to button. My mother said I asked her in wonder why the button couldn’t be fastened.

I think my current love for making and tinkering with things comes from my parents’ influence during this time.

When I was five years old, I entered school with my sister who was one year older. My sister entered the first grade, and I entered the pre-elementary class. I’m not sure how it is now, but at that time in China, even elementary school students could be held back or skip grades, so my sister and I entered elementary school one year earlier than others. I liked studying, especially math. I often got the top score on tests. However, I was not good with homework and was often scolded for forgetting it. This habit didn’t improve even after I came to Japan, and I was still often scolded for it.

More than 20 years after my grandmother’s return to Japan, when I was nine years old, my parents decided to move to Japan.

New Land

With the help of my grandmother’s relatives for the necessary procedures, in October 1995, our family decided to move to Japan, leaving behind my second oldest sister who was in college at the time. It was then that I left my small village for the first time and headed to Japan by plane from Shanghai. We traveled by bus from the village to Harbin, and then by train from there to Shanghai. The traffic lights and crosswalks I saw for the first time in Harbin were completely different from what I had imagined. I knew of the existence of traffic lights from books and knew that green meant “go” and red meant “stop,” but I didn’t understand what the yellow signal on the traffic lights I saw for the first time meant. The train from Harbin reached Shanghai in about two days. The people in Shanghai spoke a dialect with a strong accent, so I couldn’t understand what people around me were saying, and I already felt like I was in a foreign country. I seemed to have toured various places in Shanghai with my family at that time, but I hardly remember any of it.

After staying in Shanghai for several days, I boarded a plane for the first time in my life to travel to Japan. Back in the village, when an airplane passed overhead, everyone would come out of their houses to look up at it. I was excited by the thought that the plane I was about to board might pass over my village, and wondering if my friends would see me if I waved. Despite my excitement about the plane, I must have been tired and fallen asleep, as I barely remember the flight now. The only thing I remember is seeing the blue sea and green islands from the air before landing.

Upon landing at Kansai International Airport, the first place we headed was the restroom. The door of that restroom had a button that, when pressed, would open the door. Having only known primitive toilets like outhouses before, I thought I had come to an incredible future.

After arriving in Japan, we relied on my father’s acquaintance and ended up living in Tokyo. My father borrowed money for living expenses from an acquaintance and rented a run-down apartment called Iida-so in Fujimidai, Nerima Ward, which didn’t even have a bath. We settled in one room of this two-story apartment and purchased a refrigerator and a two-layer washing machine as the minimum necessary household appliances. I was very happy as we didn’t have either of these when we were in China. Tatami rooms, Japanese-style toilets, gas stoves for cooking—everything was new to me.

For our life in Japan, we each needed to adopt Japanese-style names. My current name, “Tatsuo Nomura,” is what I chose for myself at that time. Since I couldn’t understand Japanese at all then, I borrowed the name of the protagonist “Tatsuo Hayashi” from a Japanese textbook my father had. And so our life in Japan began.

My sister, who was one year older, and I walked around the nearby parks and shopping streets almost every day. Slides, swings, phone booths, vending machines, vegetable shops, bakeries, trains, railroad crossings, tunnels—everywhere we went, we saw things for the first time, and every day was an adventure for us. While walking, we often came across various discarded items. Since we had almost no furniture, my sister and I would often pick up furniture and appliances, load them onto a bicycle we had also found, and bring them home. Bulky garbage collection points with dressers and TVs were treasure troves for us.

Soon after coming to Japan, my father started working at a construction site, while my mother found work at a dry cleaning shop. Both did manual labor as they could barely speak Japanese. Life was still poor, but with my parents’ desperate efforts, it gradually improved and became incomparably richer than our time in China. We could eat white rice every day and often had dumplings too. I always looked forward to going shopping with my parents at the supermarket on weekends, where they would buy me various snacks and juices. This was unthinkable when we were in China. I especially loved bananas and often had them bought for me. The first time I ate a banana was in China, at the home of a wealthy person I had visited with my father. Since then, I had wanted to eat a banana again, and after coming to Japan, that wish was finally fulfilled.

Once, my father took our family to the observation deck of Sunshine 60 in Ikebukuro. Back in China, there wasn’t even a single two-story building in my village, so I couldn’t imagine what a 60-story building would be like. Looking down from the observation deck with a view of all of Tokyo, I felt proud to be in such a high place. I sensed that life could get better with effort, even as a child.

Although I was still a child, my memories from that time are vivid, and I still remember the address, our home phone number, the scenery of the neighborhood, the stores, and even the phone numbers of friends from that time.

A few weeks after coming to Japan, my sister who was one year older and I were to enter elementary school.

Cultural Barriers

The first school I entered after coming to Japan was Shakujii Higashi Elementary School in Nerima Ward. It was on a day a few weeks after we had arrived in Japan and our life was beginning to settle down. My mother, my sister, and I, along with a colleague of my mother’s who came as an interpreter, went to greet the principal. Since my sister and I had entered elementary school one year earlier, I was already in the 4th grade in China, so I wanted to be placed in the 4th grade in Japan as well. However, this was not allowed, and my sister and I were enrolled in the 3rd and 4th grades respectively. On the way home that day, we stopped at a stationery store at the corner to buy writing supplies. My sister and I were dying to have the so-called multifunctional pencil cases with cool gimmicks like hidden doors. However, after discussing between ourselves, we decided to ask for the cheapest metal pencil case. We were well aware that our family didn’t have much money. That pencil case made a loud noise when dropped, which often embarrassed me at school. My father got a hand-me-down schoolbag from a friend’s child, which was worn out and tattered. With these preparations complete, my elementary school life in Japan began.

Although I started attending school, I couldn’t speak any Japanese as I had just arrived in Japan. Fortunately, there was a boy named Tobari who was in a similar situation, having come to Japan from China about half a year before me, and he taught me various things. The school also welcomed a new Japanese teacher, Ms. Abe, who could speak Chinese, for us. Thanks to having time to learn Japanese from Ms. Abe in addition to regular classes, both my sister and I were able to speak Japanese almost as well as the children around us after about half a year in Japan. Children of this age absorb quickly and can learn any language immediately, and conversations between my sister and me unconsciously switched from Chinese to Japanese. However, since our parents could only speak Chinese, we continued to speak Chinese with them. Being the best Japanese speaker in our home, I was often dispatched to various places to interpret for my parents. I frequently went alone to places like the ward office for various procedures.

I learned Japanese without much time to feel the language barrier, but I often encountered cultural barriers. For example, there was no school lunch in China, so eating lunch together with everyone was a new experience. The dishes served in school lunch were all things I had never eaten before, but everything was delicious, and I asked for seconds every day. The first time I asked for seconds, it was still before the time when seconds were allowed, so I was scolded, and when I returned what I had taken to the pot, I was given very disapproving looks. I realized I had done something wrong again and felt down. I was also often made fun of for always wearing the same clothes. In the rural area of China where I grew up, having only a few pieces of clothing was normal, so wearing the same clothes was common. What I hated most were days when we had to bring lunch boxes, like for field trips. Unlike my classmates’ elaborate lunch boxes, mine contained only simple rice and one side dish. I was so embarrassed to have my lunch box seen by my classmates that I would try to eat it away from others’ eyes.

However, not everything was bad. Once, I got into a fistfight with a classmate named Nakajima, though I don’t remember the reason well. During the next break time, Nakajima came to me, and to my surprise, he said, “I’m sorry about earlier.” Having never experienced apologizing or being apologized to after a fight in China, I was shocked. I also apologized saying, “I’m sorry,” and we made up. Similarly, I learned the importance of being considerate of others when my homeroom teacher taught me to hand scissors with the handles facing the other person to prevent injury.

I believe these Japanese feelings of consideration for others, which I learned while experiencing cultural barriers firsthand, had a positive influence on me as a child.

Encounter with Video Games

It was also around this time, after entering elementary school and gradually making friends, that I first encountered video games. Even in China, I somewhat knew of the existence of video games, but I didn’t understand the details. There seemed to be places like arcades, but elementary school students were forbidden to enter, so I didn’t know what was inside. The first time I played a video game was when I visited the home of a friend named Sano during my time at Shakujii Higashi Elementary School. Sano was a boy who owned various software, and I remember playing Super Nintendo games with him such as “Super Mario World,” “Super Bomberman,” “Super Donkey Kong,” “Super Mario RPG,” “Ganbare Goemon,” “Kirby’s Dream Land,” “Dokapon 3-2-1,” “Momotaro Dentetsu,” “Super Mario Kart,” and “Street Fighter II.” I immediately became engrossed in video games. Since I didn’t own any video games myself, I was always allowed to play at Sano’s or other friends’ houses.

Once, Ms. Abe, who had been teaching me Japanese, gave me a Famicom (Nintendo Entertainment System) that her children had played with when they were young but no longer used. At that time, the PlayStation had already been released, so hardly anyone played with the Famicom anymore. Along with the Famicom, I received “Dragon Quest,” but I didn’t know how to play it. In the first stage of Dragon Quest, following the king’s instructions, you have to pick up a key from a treasure chest and use that key to get outside, but this was difficult for me as I was still struggling with Japanese. I had a friend who lived nearby come over to teach me how to play, and that’s when I first learned how fun Dragon Quest was. Of course, I had no idea that this would later lead to Google Maps 8-bit. At that time, Google hadn’t even been founded yet.

Playing with friends around me like that, I gradually became more and more immersed in video games. In 1996, when I was in the 4th grade of elementary school, I was playing games at a friend’s house as usual. That day, I had gone to the house of a girl named Suzuki. Suzuki always had new games, and her house also had air conditioning, so I often visited. That day, Suzuki let me play a new Game Boy game she had just acquired. That game was different from any game I had known before. While the games I had played until then all involved defeating enemies or monsters in one way or another, in this game, you could actually make these enemy monsters your allies. As you raised these monsters that had become your allies, they would become stronger and stronger, learning new techniques, and even evolving if you raised them further. That game was “Pocket Monsters,” or “Pokémon” for short. I was so captivated by it that I stayed at my friend’s house until late that day, and was almost forced to leave. Even afterward, I was still preoccupied with Pokémon and frequently visited Suzuki’s house. Perhaps taking pity on me, the kind Suzuki lent me her Game Boy along with “Pokémon.” Since the Game Boy didn’t have a backlight, I would attach a “Light Boy” to illuminate the screen from above, and I would often play late into the night, hiding under the covers.

When the anime “Pocket Monsters” began broadcasting on TV Tokyo in April 1997, Pokémon popularity reached its peak. School was always full of Pokémon talk. We would sing Pokémon songs together, draw pictures, and everyone would talk about their favorite Pokémon. Besides the Pokémon TV anime, I also watched a program called “64 Mario Stadium” that aired on the same channel every week. I always looked forward to a popular segment within the program called “Pokémon League.” This segment involved children gathered through applications forming teams of three to battle in “Pokémon” via link cable, and the winners would receive “Pokémon Blue” with the mythical Pokémon “Mew” as a prize. Since I was still playing “Pokémon” borrowed from a friend, I thought I might get my own “Pokémon” if I participated, so I decided to apply. Unfortunately, my application was rejected, but I received an invitation from TV Tokyo to observe the recording, and I ended up going to watch. I remember being grateful for TV Tokyo’s consideration at that time. Guided by a friend’s mother, several of us went to TV Tokyo’s recording studio, which was near Tokyo Tower at that time. I entered the studio I had always seen on TV and watched the recording from the audience seats. It seems that day was the birthday of Toru Watanabe, who was the host of the program, and I remember him being presented with a bouquet of flowers from co-host Noriko Kato after the recording. When that recording was broadcast, I was proud to see myself appearing behind the hosts and boasted to many friends. However, I never did get my own “Pokémon.”

Back to the Countryside

Just as I was finally getting used to life in Japan, another major turning point arrived. The cost of living in Tokyo was high, and the wages weren’t good, so my parents were looking for a different life. I often went to the employment office with my father or accompanied him to interviews, but we couldn’t find a good job. In this situation, my father happened to find a garbage collection job in Nagano, where he had gone to meet a friend. The salary wasn’t bad, and the company president was a person of character who was understanding of foreigners. Also, the cost of living in Nagano was significantly cheaper than in Tokyo, so we decided to move there. I didn’t want to move as I had finally grown accustomed to life in Tokyo and had made friends, but there was no choice. It was in the autumn of 1997, when I was engrossed in “Pokémon.”

When we moved to Nagano City, I thought, “What a rural place this is,” unlike Tokyo, with fields in the neighborhood and no tall buildings. Compared to the cold village in Heilongjiang Province where I originally lived, Nagano City was also a big city, but having just gotten used to life in Tokyo, I was impertinently felt Nagano to be rural. In reality, Nagano was bustling with activity as it was preparing to host the Winter Olympics the following year.

After staying at my father’s friend’s house for about a month, we finally settled in a city-run housing complex. I transferred to a nearby school called Yuya Elementary School. When I first introduced myself to the class, I mentioned that I was Chinese. I was worried that saying I was from China might lead to bullying or being pointed at behind my back, but I didn’t want to hide it. In Nagano, which was preparing for the Olympics the following year, there were other foreigners too, but I could feel the difference in attitudes and reactions of Japanese people toward Westerners versus Chinese people. It seemed to me that both adults and children had a consciousness that English was cool and Chinese was uncool. Sometimes I was told that I didn’t understand certain things because I was Chinese. At that time, among people like me who had come from China to Japan at a young age, there were not a few children who stopped speaking Chinese because they disliked being pointed at behind their backs by others. As a result, after time passed, they really became unable to speak Chinese. I never hid the fact that I was born and raised in China. I think that even as a child, I wanted to assert without shame that being born and raised in China was part of who I was. Although I didn’t know the term at the time, I definitely had a strong sense of identity. I believed that denying being born and raised in China was denying myself. Rather, I thought it was something to be proud of that I could speak two languages. Perhaps the name “Shi Lei” given to me by my mother gave me this strong spirit.

Contrary to my concerns, I wasn’t teased for being Chinese and quickly made friends after transferring. Sometimes I received sarcastic comments about being Chinese, but nothing worth noting. And of course, what I played with my new friends was video games.

Behind the Games

When I became a sixth-grader, my oldest sister, who was also born in the Year of the Tiger among my four sisters, bought me a new schoolbag, a Game Boy, and “Pokémon Red.” I finally had my own “Pokémon.” The first Pokémon I chose was Charmander. I was absorbed in running around the Kanto region with Charmander, defeating gym leaders like Brock and Misty. I acquired new Pokémon like Rattata, Pidgey, and Clefairy, and expanded my team. Wild Abra would immediately teleport away, so it took me many days to catch one. The Pokémon that appeared were slightly different from the “Pokémon Green” I had borrowed from Suzuki before, and as I progressed to new towns, there were new Pokémon, so there was always excitement. By the time I had defeated the eight gym leaders and advanced to the Champion Road, my Charmander had evolved into Charizard. Even after defeating the Elite Four and the final boss, my rival, to become Champion, the game wasn’t over. I had to catch the legendary Pokémon “Mewtwo” who lived in the “Cerulean Cave,” which only became accessible after completing the game. Even after catching “Mewtwo,” the game still continued. You hadn’t truly completed the game until you had caught all 151 Pokémon and completed the Pokédex. “Pokémon” was an innovative game packed with new ideas that kept surprising players.

“Pokémon” was also a game full of rumors. “There’s a 152nd Pokémon,” “If you ride the truck in a certain place, you can go to a village where the mythical Pokémon Mew is,” “You can catch the ghost in Lavender Town.” These urban legends were popular among elementary school students. What further fueled these rumors was a bug technique called “Select BB.” Using this bug technique, you could suddenly raise Pokémon to level 100, get infinite items, and even acquire the mythical Pokémon “Mew.” However, using the bug technique often corrupted save data, making it impossible to continue the game. As it was the heyday of bug techniques and cheats, I often called various manufacturers’ customer service centers to ask about cheats. Of course, they wouldn’t tell me about bug techniques. Playing like that, I became strongly interested in the mechanisms behind bugs and cheats, and in how games were created in the first place.

School Events

My parents weren’t very strict with me. I was told to “study,” but there weren’t many detailed instructions. I hardly showed them my grades or notifications about school events, and I didn’t inform them about visitation days. My parents were always working, and I thought they wouldn’t understand much if they came to school since they didn’t speak much Japanese, so it wouldn’t be worthwhile for them to come. I was good at studying, so I often got 100 points on elementary school tests, but I didn’t show these to my parents either. For things that required a seal, I forged them with red ballpoint pen writing that looked like a seal. Later, when I read a book by Honda Motor’s founder, Soichiro Honda, there was a story about him forging a seal too, and I was pleased to learn that he had done something similar. This didn’t change until I graduated from graduate school, and ultimately my parents never attended any of my entrance or graduation ceremonies.

-

NHK Special: How the Manchurian Colonists Were Sent - The Awakened Materials of Kwantung Army Officers ↩