Chapter 7: Niantic and Pokémon

Niantic Labs

On March 24, 2014, a week before the launch of “Pokémon Challenge,” I received a message from Masa Kawashima, who was at Niantic Labs, then a Google internal startup. I was told that John Hanke, the founder of Niantic Labs, was interested in the internal demo of Pokémon Challenge and wanted to talk with me. John Hanke was the co-founder of “Keyhole,” which became Google Earth, and a legendary figure who had served as the head of the Google Maps team from the time Keyhole was acquired by Google until he founded Niantic Labs. John founded Niantic Labs with the belief that the world would be a better place if people went outside, connected with each other, and learned about their surroundings. Since I had never spoken directly with John before, I thought this was a good opportunity and agreed to have a video conference two days later. Masa gave me some background information about Niantic, John, and Ingress as preparation. On the day of the meeting, John, whom I was speaking with for the first time, had an impressive beard and a dignified appearance. John asked me, “Do you know about ‘Ingress’?” Ingress is an innovative game created by Niantic Labs that uses location information. Simply put, players become secret agents and are divided into blue and green teams to compete for locations called “Portals” that exist throughout the real world. These “Portals” are located at points related to art and knowledge in the real world, such as monuments, sculptures, and murals. This database of “Portals” is a unique asset that only Niantic has worldwide. To play Ingress, you need to walk around and visit these “Portals.” Ingress was created to fulfill John and Niantic’s vision of “getting people outside.” I replied, “Yes, I know it.” John then asked, “What do you think about creating a game with Pokémon that can be played in the real world like Ingress?” It seemed John had this idea after seeing the demo of “Pokémon Challenge.” A game where you become a Pokémon Trainer and catch Pokémon in the real world—anyone from my generation must have dreamed of this at least once. Thinking there couldn’t be a more exciting proposition, I agreed with John and promised to approach The Pokémon Company with this idea. After the launch of “Pokémon Challenge,” at the celebration party, I immediately discussed the collaboration with Ingress with Miyahara-san (current director) of The Pokémon Company, who was sitting next to me. Miyahara-san gladly responded that he would introduce me to the person in charge.

The Beginning

At 1:00 PM on April 6, 2014, I was in a meeting room at The Pokémon Company. With a schedule to return to San Francisco at 5:00 PM that evening from Narita, I managed to arrange a last-minute meeting with Utsunomiya-san (Takato Utsunomiya), who was the Director of Mobile Business (currently Representative Director and COO). According to Utsunomiya-san, this mobile application division had just been established a few days prior, and The Pokémon Company was just beginning to undertake mobile application initiatives. I showed Utsunomiya-san the promotional video for “Ingress”1 and explained what kind of game it was. Then I strongly advocated for creating a Pokémon game using this Ingress technology. From Utsunomiya-san’s neutral expression, I couldn’t tell at all whether he was interested or not. With my flight time approaching, I left the place not confident whether this sales pitch had been successful.

Since I wasn’t yet a member of Niantic at that time, I handed over the responsibility to Masa. From that point, Masa took the lead in advancing the project. After some email exchanges between The Pokémon Company and Masa, it was decided that John would visit Japan in May to speak directly with The Pokémon Company. Masa from Niantic Labs, Business Development Director Daniel Lederman, and I, who was still a Google Maps engineer at that time, accompanied him on this business trip. During the meeting, President Ishihara of The Pokémon Company hit it off with John, and there were signs that a new project would begin. After the meeting, a dinner was arranged with Ishihara-san. I reintroduced myself and summarized my background—exactly what’s written in this book—from my upbringing, my encounter with Pokémon, my encounter with computers, to my work at Google, all in about five minutes. According to an interview article with Ishihara-san that I read later, he was impressed by my self-introduction at that time, and it became one of the reasons why he decided to entrust me with the “Pokémon GO.”

Sometime after this meeting, Masa asked a Google Japan employee to organize an Ingress workshop targeted at The Pokémon Company. Ishihara-san became completely hooked on Ingress and deeply resonated with the concept of “going outside, exploring the world, and connecting with people,” feeling a philosophy common to Pokémon. Ishihara-san reached level 8, which was the highest level at that time, in just a few weeks, completely transforming into a veteran Ingress agent.

In June 2014, The Pokémon Company and Niantic Labs held a meeting regarding specific game content at Google headquarters in Silicon Valley. From The Pokémon Company, Ishihara-san, Utsunomiya-san, Hirobe-san, and Furuya-san participated, along with CEO Okubo-san, Kamai-san, and David-san from The Pokémon Company International, the American subsidiary of The Pokémon Company. Masuda-san, who is the Director of Development and Board Member at Game Freak and has been involved in development since “Pokémon Red and Green,” also participated. From Niantic Labs, John, Daniel, Masa, and others, including Dennis, who later became the Art Director for “Pokémon GO,” participated. I was still with the Google Maps team but joined as a 20% helper. At this time, Ishihara-san commented, “Ingress is extremely interesting. This new form of play using location information has a universal appeal that can be accepted worldwide. However, my honest impression is that the threshold for fully understanding its fun is high, and the entrance is narrow. If we combine it with the world of Pokémon and broaden the entrance, I feel it has the potential to spread rapidly. I believe we can create something interesting if we can build a system centered around the simple experience of ‘catching Pokémon’ in various places that can be enjoyed for a long time.” With these words, he declared the partnership with Niantic Labs. The idea for the “Pokémon GO Plus” device, which would later be released by Nintendo, was also mentioned by Ishihara-san during this meeting. Masuda-san presented a proposal based on Ingress, and the collaboration between Ingress and Pokémon began to take on a realistic form. Later, John reflected, “It was the best meeting we had with external partners since Niantic was formed.”

At the reception desk in Google’s office

At the reception desk in Google’s office

As a side note, one of the employees at the Google reception desk happened to be a Pokémon fan and had arranged Pokémon paper crafts at the reception. When they learned that the visitors were Ishihara-san and Masuda-san, they were thrilled and took commemorative photos together. Everyone present was reminded of the widespread popularity of Pokémon.

Product Manager

Regular meetings between The Pokémon Company and Niantic Labs were established, and the direction of the game was determined through weekly video conferences. I continued to participate in the meetings as a 20% project. The following points were also decided through these discussions:

● Exploring a different gameplay style from the main Pokémon games so players wouldn’t need to look at their smartphones frequently

● Creating a broad but shallow monetization structure to allow more players to enjoy the game

● Making it a game about catching lots of Pokémon

● Having Masuda-san be responsible for music and sound

● Creating a game that gets people outside

● Having Niantic Labs lead the development

Thus, as the project was finally getting into full swing, after one of the meetings, I received a personal message from Utsunomiya-san. He asked me to “take on the role of Game Director for ‘Pokémon GO’.” Since there was no Game Director position within Google, I wasn’t sure what that role entailed. After learning more, I understood it was equivalent to a Product Manager role at Google. At that time, my position was Software Engineer, so transitioning to Product Manager meant giving up engineering. Later, when I received a similar offer from John, I asked for some time to think it over. I had no experience as a Product Manager before, and if I had continued as a Software Engineer in the Google Maps team, my next promotion was already in sight, and my salary would have continued to increase year by year, so I hesitated a bit about this career change. When I consulted with Masa about this, he said, “Let’s go to lunch,” and took me to a Japanese curry restaurant on Castro Street, about a 20-minute drive from the company. While eating curry, Masa told me a lot about Niantic. “Niantic has legendary people like John and Dennis!” “When Pokémon and Ingress come together, it’s going to be an amazing game!” “Come to Niantic and let’s do this together, Tatsuo!” Throughout the meal, he spoke with enthusiasm that rivaled the spicy curry I had ordered. With Masa’s encouragement and after much consideration, I concluded, “This is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to turn a project I started as an April Fools’ joke into a real product. I’ll surely regret it if I don’t do it.”

In October 2014, I officially transferred to Niantic Labs as a Product Manager to lead the “Pokémon GO Project.”

Meeting Iwata-san

About two months after joining Niantic Labs, in December 2014, John and I, who were on a business trip to Japan, had an appointment to meet the late Iwata-san, who was then the President and CEO of Nintendo, through an introduction by Ishihara-san of The Pokémon Company. Iwata-san was also a graduate of Tokyo Institute of Technology like me, and there was a connection that he had once worked with Professor Matsuoka, my academic advisor, to create the Famicom “Pinball” game. That day, I had decided to show Iwata-san the Famicom I had built during university. I had been waiting for this opportunity since I first met Iwata-san in Kyoto. My handmade Famicom, which had been mailed from my parents’ home, had several disconnected wires, but I hurriedly repaired it with a soldering iron and managed to get it working before meeting Iwata-san. When I met Iwata-san, I set aside all talk about “Pokémon GO” and enthusiastically explained to him about the Famicom I had built. Iwata-san, who seemed to find it difficult to comment, responded with, “I see. I see,” nodding along, while I excitedly continued my explanation undeterred. When I built it, I never dreamed there would come a day when I would show it to Iwata-san, so I was overjoyed.

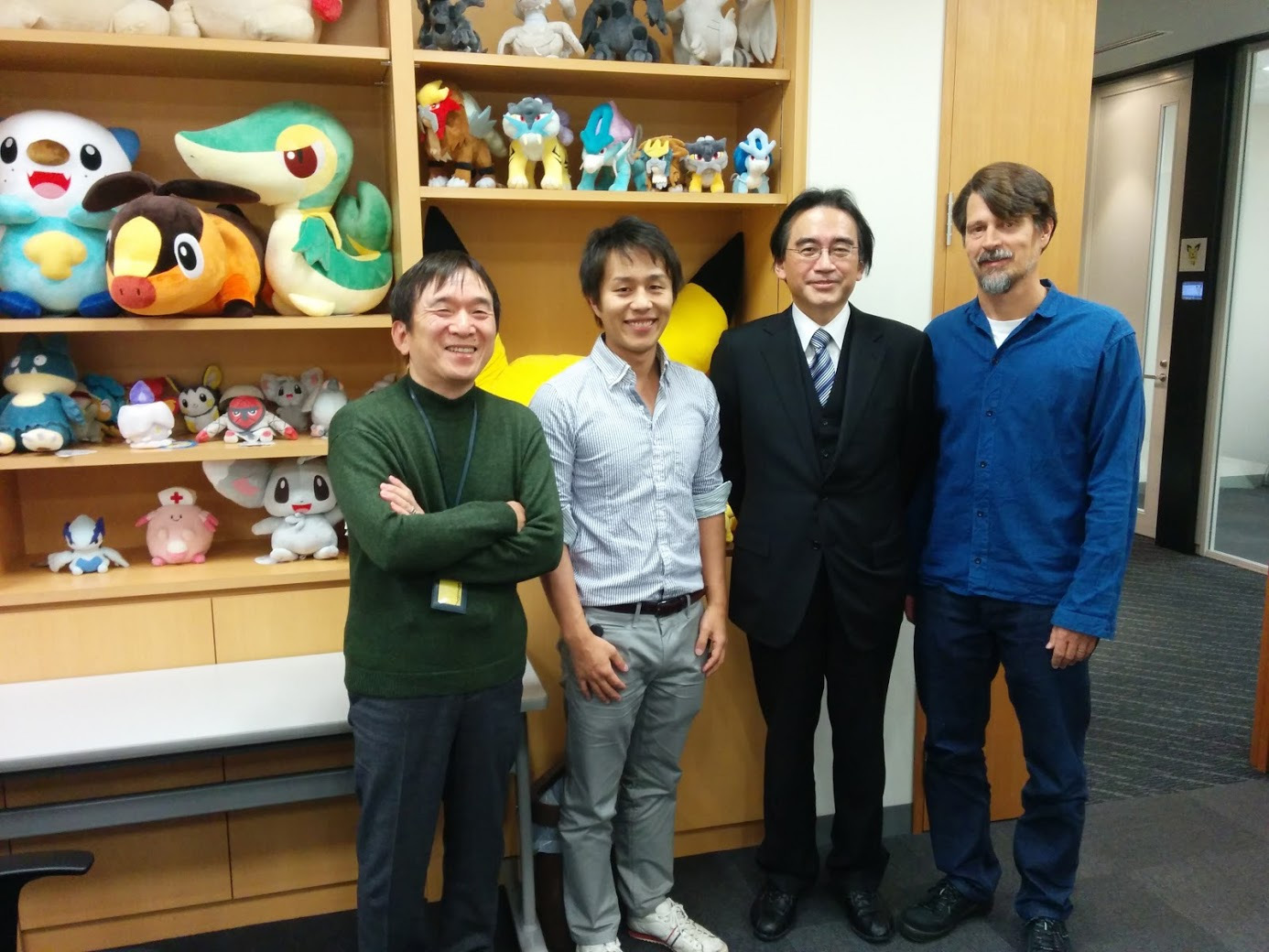

From left: Ishihara-san, me, Iwata-san, John

From left: Ishihara-san, me, Iwata-san, John

About half a year after that meeting, Iwata-san passed away suddenly at the young age of 55, mourned by game fans around the world. At that time, Ishihara-san conveyed in a message to the media, “Until just recently, we had been having meetings with Iwata-san and working together on a project. There is a strong desire to somehow complete this and show it to him, but now it’s painfully regrettable that we can no longer see that gentle, smiling face of Iwata-san. All we can do is pray for his soul.” This project was, of course, “Pokémon GO,” and I felt that I must complete “Pokémon GO” at all costs.

Niantic Inc.

In August 2015, Niantic Labs announced that it would spin off from Google and become independent as Niantic Inc. When I first heard from John that Niantic would become independent, I was a bit perplexed. I had to choose between becoming independent together with Niantic and continuing the development of “Pokémon GO,” or staying at Google and doing different work. If I stayed at Google, my salary and stability would be guaranteed, but if I became independent with Niantic, the future was completely uncertain. There was no guarantee that “Pokémon GO” would succeed. I had some hesitation, but I chose to “create Pokémon GO.” I wanted to see through the project I had started to the end. Besides, I thought that even if it failed, it would be a good experience.

The following month, in September, John, who had come to Japan, held a press conference titled “The Pokémon Company New Business Strategy Announcement” together with President Ishihara of The Pokémon Company, Director Shigeru Miyamoto of Nintendo, and Director Masuda of Game Freak. The production of “Pokémon GO” was officially announced at this press conference. The promotional video for “Pokémon GO” released at that time was viewed more than 30 million times in just a few days2. (Actually, there’s a scene in this video that lasts less than a second showing Masuda-san and me having a Pokémon battle on Game Boy.) The production of this video was once again handled by Motoyama-san from Six. This was the fourth collaboration between Motoyama-san, Suga-san, and me since “Dragon Quest Map.”

In October, Niantic officially became independent, and the “Pokémon GO” team was reorganized. Dennis Hwang became the Art Director, Ed Wu became the Engineering Director, and I continued to serve as the Product Manager and Game Director. Keiichi Kawai-san, who had been the Product Manager for Street View at Google, also newly joined Niantic as my boss, and the furious development resumed.

Field Test

In March 2016, the “Pokémon GO” field test began. This field test was a test to have many people play during the development stage and gather bug reports and requests for the game. At first, we intended to call it a “beta test,” but since beta tests typically refer to a state where the game is almost complete and only bugs need to be fixed, we decided to call this state, where the game was not yet complete, a “field test.” The field test was conducted in four locations: Japan, the United States, Australia, and New Zealand. Test players were recruited from Niantic’s website. From the many applicants, we initially invited Ingress players who had high literacy in location-based games. Participants were also invited to a private Google+ community, where they posted various feedback. The feedback from the test players was surprisingly high in quality, with reports of specific issues and even game ideas being proposed. Positive feedback like “fun” and “cool” was supportive. At the same time, there were many opinions like “Is this a game?” and “I don’t understand.” It was very helpful to see players discussing among themselves about what specifically was not fun and what improvements could be made.

For example, there are items called “Pokémon Candy” and “Stardust” that are necessary for raising Pokémon, but these did not exist at the start of the field test. Since we wanted to make “Pokémon GO” a game about catching lots of Pokémon, we thought it would be difficult to balance raising Pokémon and catching many of them. However, we received a lot of feedback from players wanting to raise their Pokémon, and after much struggle, we came up with Pokémon Candy and Stardust. With the addition of these two items, the gameplay of “Pokémon GO” was significantly enhanced.

The feel of throwing a Poké Ball was also a frequent issue. Converting the two-dimensional swipe motion of a finger on the screen into the trajectory of a three-dimensional Poké Ball was challenging, making it difficult to create a “realistic” sensation. We had designed it so that when you throw with force, it flies far, and when you throw gently, it flies nearby, but it required quite precise operation to hit Pokémon accurately, so we often received feedback that “it doesn’t hit at all.” In particular, a Pokémon called “Golbat” was known as a Pokémon that balls would never hit because it was positioned far away. So, we created a parameter that could adjust the trajectory of the ball on a scale from 0% to 100%. At 0%, there would be no adjustment, and at 100%, the adjustment would always make the ball hit the Pokémon. We adjusted this value while observing player reactions. This was a part that Masuda-san was particularly particular about, and we rebuilt it many times with his advice.

It was also often mentioned that player levels in the game didn’t increase easily. Based on this data, in the final version, we increased the maximum level from 16 to 40, allowing players to level up more frequently.

This field test continued until about a week before the launch. During the last week of the field test, we made Pokémon spawn in massive numbers as if it were a festival. Even Snorlax and Lapras, which had rarely appeared until then, were appearing with considerable frequency. Since the field test data would not be carried over to the official version, this massive spawn became a lasting memory of the field test.

The Birth of Pokémon GO

At 2:00 PM on July 5, 2016 (U.S. West Coast time), with all preparations complete, surrounded by Niantic members gathered in the conference room, I pressed the launch button. Two years from “Pokémon Challenge,” and 20 years since the birth of “Pokémon,” it was the moment “Pokémon GO” was born. That day was a limited release in Australia and New Zealand. We started from places with relatively low participation in the field test to observe the load on the servers. Although it was early morning in Australia and New Zealand, talk about “Pokémon GO” gradually began to appear on the internet. That day passed without any major issues, and after monitoring the situation to some extent, everyone went home.

The moment of pressing the launch button

The moment of pressing the launch button

The next morning, during the regular meeting, Engineering Director Ed showed everyone the latest server load and said, “At this rate, it will be 10 times what we initially anticipated.” Everyone was half-skeptical, and I also thought, “Surely that can’t be right.” However, it seemed that “Pokémon GO” had already become a big topic in Australia and New Zealand, with pictures of crowds of people going out into the streets and playing “Pokémon GO” being published in various media outlets on the internet. As planned, we released “Pokémon GO” in the United States that day. Immediately after the release, all the graphs monitoring server traffic began to rise sharply. It was also picked up one after another by internet media, and on Twitter, topics about “Pokémon GO” were being tweeted incessantly. Unable to withstand the sudden load, the servers crashed multiple times. The server team led by Ed stayed glued to their screens, dealing with problems that kept arising one after another. With many of Niantic’s engineers, including Ed, being former Google employees, they were originally adept at handling services that deal with hundreds of millions of people. The “Pokémon GO” servers were also designed to handle billions of users. Nevertheless, it was the first time that a large number of users had actually logged into the server simultaneously, so various implementation issues came to light. Due to the solid design, the implementation issues that emerged were all solvable.

Following the launch in the United States, we successively launched the service in European countries like Germany and the United Kingdom. Slightly delayed from the initial schedule, we launched the service in Japan on July 22. The game became a major topic of conversation wherever the service was launched, and it dominated the top spot in app store download rankings for several weeks. “Pokémon GO” continued to grow, and as of June 2017, it had been released in more than 150 countries and regions, including Southeast Asian countries, African countries, and South American countries, with more than 750 million downloads. The sight of Pokémon Trainers going outside to play all over the world was a realization of Niantic’s vision of “getting people outside.”

On the weekend of the week “Pokémon GO” launched in the United States, I came to a seaside boulevard to play “Pokémon GO.” Most of the people passing by were playing “Pokémon GO” with smartphones in hand. I approached various people asking, “What did you catch?” “Where did you find that?” Seeing so many people enjoying “Pokémon GO” right in front of me, my heart was filled with joy.

Some of the stories highlighted in letters received by Niantic and in media reports further encouraged me. Among them, when I learned from an internet post by a parent about an autistic child who started going outside and was able to talk to strangers because of “Pokémon GO,” tears flowed. Knowing that what I had been doing could have even a small positive impact on someone else’s life made me feel that all the hard work had been worthwhile. Of course, with so many people playing, problems also pile up. Many people flocking to small parks and similar places disrupted the peaceful lives of local residents, and some people were involved in accidents. Since the launch, we have made improvements to make the game as safe as possible, such as adding speed limits to gameplay and changing how Pokémon appear, and I believe we must continue to make improvements.

Twenty years after first encountering “Pokémon,” I, now an adult, was able to let people around the world experience the shock and excitement I felt when I first encountered “Pokémon.” Just as I encountered “Pokémon” as a child, surely someone among the children who encountered “Pokémon GO” will further evolve “Pokémon” 20 years from now in the future.